Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire by Edvige Giunta and Mary Anne Trasciatti, Editors (New York: New Village Press, 2022)

Talking to the Girls: Intimate and Political Essays on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire by Edvige Giunta and Mary Anne Trasciatti, Editors (New York: New Village Press, 2022)Every year, the anniversary of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire comes around and with it, a commemoration of the workplace tragedy. Organizers put a great deal of effort into these events that take place outside the building where the fire raged on Greene Street, in Greenwich Village, and claimed 146 lives. The event serves as a bridge between the fateful day that served as a catalyst for workplace reforms and current tragedies that continue to claim the lives of workers.

Long after the shirtwaist disappeared as an indispensable part of a woman’s daily attire, the trail of the Triangle fire is still long and it continues to resonate in ever-widening circles. Talking to the Girls, a book of essays edited by Edvige Giunta and Mary Anne Trasciatti, brings together disparate voices that recount their connection to the fire and demonstrate the impact of the event that took place 111 years ago.

In the Introduction, the editors provide the rationale for the book, expressing their desire to bring together a diverse community “that transcends temporal, national, geographic, ethnic/racial, gender, and class boundaries.” (2) They write that, “this community understands that the meaning of history is found in the realization of its continuous relevance to the present and for the future.” (16) Each contributor was invited to write a personal essay to explain their connection and to answer the question: “Why did you gravitate toward the Triangle fire? Why is it important in your life?” (17)

The book is organized into sections – witnesses; families; teachers; movements; and memorials. The first of the witnesses, Annie Rachele Lanzillotto, dedicates her essay to Diane Forturo, “a Triangle worker who jumped from the ninth floor and survived for two days.” (25) An author, poet, performance artist and activist, Lanzillotto is a founding member of the Remember the Triangle Fire Coalition, which first sprang into action in April 2018. “Our operative verb became to remember … we all agreed to … join ranks and to nudge our city to remember and to act upon that memory.” (31-32) Out of this came the chalking of sidewalks in memory of the victims; a memorial being added to the front of the building on Greene Street, the centennial celebration of the fire; the shirtwaist kites carried by schoolchildren at the commemorations, conferences, and more. All of this to make visible the lives lost – the “seamstresses who earned a dime an hour on twelve-hour shifts.” (33) She writes about the class-collaboration and intersectionality of movements that strengthens coalition building and develops resources and political sway. It was just such a collaboration that brought the uptown upper-class women active in the suffrage movement to the aid of the union movement.

Essayist Tomlin Perkins Coggeshall offers witness to an episode from his youth, when, at age five, his grandmother allowed him to descend from a window on a rope ladder with multiple wooden crosspieces, a ladder she kept under her bedroom window in a cardboard box. The grandmother, Frances Perkins, was forever affected by the scene she witnessed on March 25, 1911. Her grandson writes that, for Perkins, “the fire became a catalyst for her work to promote widespread social change.” (47)

As a young girl growing up in Pittsburgh, Paola Corso learned to sew. In her essay, she remembers herself at age 14, “sitting at a sewing machine – the same age as Kate Leone and Rosaria Maltese – the youngest Triangle Shirtwaist Factory workers to die in the fire. I’m in a classroom, not in a sweatshop.” (79) She writes about the possible dreams of the Triangle victims; of her immigrant father who crossed the ocean in steerage and passed through Ellis Island –who escaped his fire in the steel mills of Pittsburgh, “determined to prove he was an honest Italian man with no Mafia ties.” (84) Corso’s connection to the Triangle came about when she learned the story of Frances Perkins. “Perkins inspires me.” (86) As a writer, her subject matter moves on from the steelworkers in the toxic coal-fired furnaces in Pittsburgh’s Golden Triangle to the Triangle fire. “How to write about the shirtwaist factory tragedy one hundred years later and recapture the urgency, the emotional impact Frances Perkins experienced as an eyewitness?” (86)

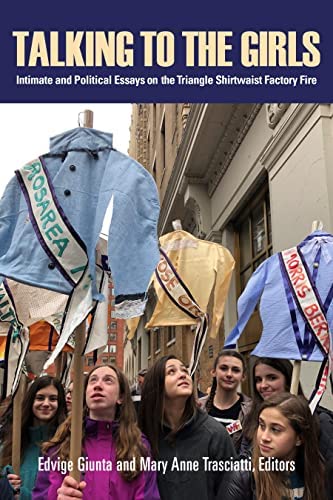

One sparkling essay is entitled, “Teaching the Triangle Fire to Middle School Students,” by Kimberly Schiller, an executive board member of the New York Labor History Association. One of her passions is to introduce her students to history. “Throughout her years as a teacher, Kimberly has taken over two-hundred students to the site of the Triangle fire.” (133) A photo taken on a trip in 2019 by Kimberly to the Triangle commemoration graces the cover of the book, showing her eighth-grade students with their shirtwaist kites aloft, all from the J. Taylor Middle School in Huntington, Long Island. She writes: “As I continued researching the history of the fire, I was moved by what Frances Perkins wrote. The tragedy was ‘seared on my mind as well as my heart – a never-to-be-forgotten reminder of why I had to spend my life fighting conditions that could permit such a tragedy.’” (161)

The historian Annelise Orleck contributes an essay entitled, “Triangle in Two Acts: From Bubbe Mayses to Bangladesh.” In her essay, she travels from the white-haired denizens of the Brighton Beach Boardwalk, survivors of history’s calamities – the Warsaw ghetto, the Stalinist purges – (137) to the Bangladesh garment workers, who “began to fight in earnest in 2006 and within a few years were joined by hundreds of thousands of Cambodian and Burmese garment workers, women in India and Ethiopia and Honduras.” (151)

There are a wealth of stories and expansive essays that bring in contemporary issues, especially housing and gentrification. A kaleidoscope of history that came to have a home within the hearts of these contributors, who share their personal reflections about the devastating events of 1911 and its legacy.

Reviewed by Jane LaTour, the author of Sisters in the Brotherhoods: Working Women Organizing for Equality in New York City. LaTour is working to complete her second book, an oral history about rank-and-file reformers — activists in the cause of union democracy.