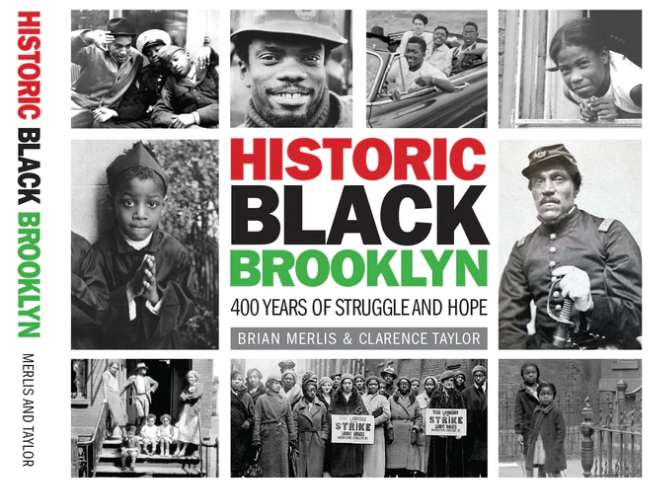

Historic Black Brooklyn: 400 Years of Struggle and Hope

Historic Black Brooklyn: 400 Years of Struggle and Hope, by Brian Merlis and Clarence Taylor (Brooklyn, NY: Israelowitz Publishing, 2021)

Historic Black Brooklyn: 400 Years of Struggle and Hope, by Brian Merlis and Clarence Taylor (Brooklyn, NY: Israelowitz Publishing, 2021)

Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was born in Puerto Rico in 1874 and after being told by his fifth-grade teacher “there is no Black history” he promptly dedicated his life to documenting that which didn’t exist. In 1926 he was paid $10,000 for his collection, which more than doubled the entire Black history collection of the NYC Public Library. Mr. Schomburg promptly used the $10,000 payment to finance additional collection work overseas. It is estimated that his contribution included 5,000 books; 3,000 manuscripts; 2,000 etchings and paintings; and several thousand pamphlets. He would later become curator of the collection in its home at the library branch on 135th Street in Harlem, which has vastly expanded from its original building (where both Langston Hughes and Ho Chi Minh studied) as it now houses over 11 million items and is known as the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Schomburg came to the U.S. at the age of 17 and moved to 105 Kosciusko Street in Bedford-Stuyvesant (“Bed-Sty”), Brooklyn in 1918. He died in Brooklyn in 1938 at Madison Park Hospital on Kings Highway (now known as Maimonides Midwood Community Hospital) after getting dental surgery. He is buried in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery and lives on in the 2020 “Forever” stamp issued by the U.S. Post Office for the “Voices of Harlem” series.

Why mention the late, great Arturo Schomburg? Because his life is an indictment of how Blacks have been left out of history and what to do about it and this book is a magnificent example of continuing Schomburg’s great legacy. And every New York City historian worth his or her salt has spent countless hours at the Schomburg Center, a true treasure.

“Historic Black Brooklyn: 400 Years of Struggle and Hope” is so rich in pictures and historical text that you just want to pore over it again and again and again. The Black history of Brooklyn is a subject suppressed and ignored by both mainstream historians and the public education system. You immediately feel the tremendous love and work that went into such a great picture collection and the accompanying text that brings historic Brooklyn back to life. It is also refreshing to see one-hundred-year-old pictures at a time when no one was taking a selfie of themselves.

You will learn that world-famous composer Eubie Blake lived in a beautiful 1880s rowhouse (still well-preserved today) in Stuyvesant Heights (284A Stuyvesant Avenue near Jefferson Avenue). While his address in Harlem on Striver’s Row is well-known (236 West 138th Street), he lived on Stuyvesant Avenue in Brooklyn in parts of five decades (1946 to 1983).

The authors talk about the British taking over Dutch New Amsterdam in 1664 and being much more brutal toward Blacks and the institution of slavery than the Dutch had been. Kings County was established in 1683 and fifteen years later almost all the county’s 296 Blacks were enslaved. By 1700 293 slaves represented 15% of Kings County’s total population. Over 3,000 enslaved and free Blacks would flee New York during the American Revolution and settle in England and its colonies.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the famous abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, of the Plymouth Congregation Church in Brooklyn Heights, held mock slave auctions to demonstrate the horrors of slavery and raised money to purchase the freedom of young female slaves. Runaway slaves were housed in the basement of his Orange Street church along the route of the Underground Railroad. And if his name is familiar, it is because in 1852 his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, which President Lincoln once credited for starting the Civil War.

The section on Black churches tells the story of Bernard J. Quinn of Our Lady of Mercy Church in downtown Brooklyn. As a White man he saw the racism and exclusion of Blacks by White churches in 1910s Brooklyn. The bishops refused to listen to him but he persisted and eventually presided over Our Lady of Mercy Church at Schermerhorn Street and then a more permanent home on the southeast corner of Ormond Place and Jefferson Avenue in the heart of the Black community. As a monsignor Mr. Quinn founded the Brooklyn Diocese’s first orphanage for Black children in a farmhouse at Wading River, Long Island. The orphanage would soon be burnt down by the Ku Klux Klan, which was very active in Long Island, rebuilt, burnt down again the following year but rebuilt again. The organization, still operating today, Little Flower Children and Family Services, was founded in these original buildings.

In the 1960s Brooklyn’s Black ministers were very active politically. Ministers Gardner C. Taylor and William A. Jones combined with Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. to form the Progressive Black National Convention. Soon after 700 people were arrested for protesting the lack of hiring of Blacks for construction of the Downstate Medical Center on Clarkson Avenue.

Elizabeth and James Gloucester were a very active Black couple with six children (that will keep you busy). He was a Clergyman at the Siloam Presbyterian Church starting in 1849, which stood for over 60 years on Prince Street between Myrtle and Willoughby Avenues. Elizabeth was a wise investor in real estate. Siloam Church financed an underground railroad and hosted many Frederick Douglass lectures at the church. John Brown spoke at the church as well and was very close to the Gloucester family. In 1858 Mr. Brown came to N.Y.C. to speak and raise money for his upcoming raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry. He stayed with the Gloucesters for a week before leaving for Harpers Ferry.

“Goodbye, Sister Gloucester. I’ve only sixteen men, but I’m to conquer,” said Mr. Brown. The rest is history and while John Brown was considered a terrorist and was hanged by the State of Virginia in December 1859 his name will adorn the West Virginia 2016 state nickel forever (West Virginia didn’t exist when John Brown led his slave uprising, but Harpers Ferry became part of it after West Virginia’s creation).

The authors cover the Bed-Stuy Restoration Corporation, created by Senator Robert Kennedy in 1967 to fund housing and businesses to the tune of $7 million (that’s equal to almost $63 million today) in Bed-Stuy. It soon created the Center for Art and Culture that includes the Billie Holiday Theatre, the Restoration Dance Theatre, the Skylight Gallery for art exhibitions and a Youth Arts Academy offering cultural lessons to the area’s young students.

Other sections of this great volume include Williamsburg, Wallabout, the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Flatbush, Kensington, East Flatbush, the Flatlands, Canarsie, Coney Island, Gravesend, Sheepshead Bay, East Brooklyn, Brownsville, Prospect Heights, and the legacy of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Ebbets Field (and Jackie Robinson). The book has an excellent bibliography for further study and is a total pleasure to read. Though expensive at $50 it is well worth the price.

Finally, regarding the co-authors:

Brian Merlis has assembled the largest private collection of historic Brooklyn photographs and his books include “Brooklyn’s Park Slope: A Retrospective,” “Welcome Back to Brooklyn” and “Brooklyn’s Gold Coast: The Sheepshead Bay Communities.”

Clarence Taylor has a long career as a public school teacher and college professor, earning his Ph.D in American History at the CUNY Graduate Center in 1994. His books include “The Black Churches of Brooklyn from the 19th Century to the Civil Rights Era,” “Knocking At Our Own Door: Milton A Galamison and the Struggle to Integrate New York City Schools,” “Black Religious Intellectuals: The Fight For Equality from Jim Crow to the 21st Century” and “Reds At the Blackboard: Communism, Civil Rights and the New York City Teachers Union.”

Reviewed by Kelsey Harrison, a long-time historian, author and political activist.