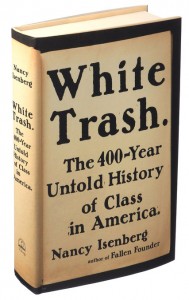

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

by Nancy Isenberg. New York: Viking, 2016

Book Review by Laura Hapke, an independent scholar whose books include Labor’s Text: The Worker in American Fiction (2001) and Sweatshop: The History of an American Idea (2004).

Nancy Isenberg, the T. Harry Williams Professor of American History at Louisiana State University, has produced a voluminous social history of a “historically toxic” (231) group: “white trash.” In so doing she has exposed the underside of American exceptionalism, the cherished national ideology of a classless society. Rather than a conventional survey of workers’ often thwarted struggles for middle class lives, however, she explores the permanent subalterns historically accused of dirtying America.

Dirt-poor white, in fact, was a tame insult compared to the epithets thrown at unfortunates from the era of British domination to our times. Hence her linguistic summary:

Waste people. Offscourings. Lubbers. Bogtrotters.

Rascals. Rubbish. Squatters. Crackers. Clay-eaters.

Tackies. Mudsills. Scalawags. Briar hoppers.

Hillbillies. Low-downers. White n—s. Trailer trash.

Degenerates. White trash. Rednecks. Swamp people. (302)

The shift in names depended less on nuances than on the temporal, spatial, and geographical realities of this economic group. In the 1600s, Britain produced colonies of people they saw as drones. Set apart by poverty, they formed a surprisingly large group of expendables. (Though White Trash appeared before the election, echoes of the 400-year-old charge can explain Trump supporters’ visceral responses to Hillary Clinton.)

Hate speech routinely was the basis for dehumanization. The Founding Fathers saw the bestial in farm hands. The Civil War era augmented the view: freed African Americans cemented their negative associations of sharecropping. A series of presidents refracted this narrative through distrust of backwoods wildness. When the promise of cheap land drew such people, the argument went, they merely replicated their laziness, crude behavior, and filthy habits rather than rise to the land-owning occasion.

Isenberg is particularly sympathetic to the families who supposedly validated the tabooed inbreeding. Rather she points out how the early modern fixation on isolated examples like the Jukes and the Kalikaks were just that.

After decades of similar thinking, the Progressive Era, in the name of enlightened moral order advanced the fake science of social engineering. The term belied the sterilization of many deemed retarded; the South was particularly effective. Whatever his positive qualities, muddying Theodore Roosevelt’s reputation is his belief in such eugenic solutions.

His descendant Franklin Delano Roosevelt is the exception to this institutionalized hatred. The author finds that the New Deal administration reversed the ideology of waste people. Dust Bowl refugees in particular were the victims of devaluation, their dignity ignored. She reminds us that agencies like the Farm Security Administration devoted their energy to confronting poverty. There was no permanent army of the poor, only unfortunates who deserved relief in both senses of the word.

She might have qualified the argument in terms of mass unionism. Manual workers such as the Okies and Arkies who benefited from government camps and monetary aid were never among the masses of industrial workers who were empowered by the Wagner Act, under which labor could organize legally.

This capsule history, of course, does not do justice to Isenberg’s meticulously detailed, closely argued, and more than 450-page social history. Whatever the people trashed by America, she chronicles the wages of prejudice. New England’s subaltern class, for example, is almost never included in studies of white degeneracy. Isenberg reminds the reader that the well-known novel by Carolyn Chute, The Beans of Egypt, Maine, was often misinterpreted as a literary expose of regional dysfunction. Reinforcing Isenberg’s own thesis, Chute defended the imagined family’s ability to create communities.

Particularly illuminating are her analyses of celebrity politicians parlaying their lowly country roots into a populism packaged for avid audiences: Lyndon Johnson, Bill Clinton, and of course Sarah Palin. In one of the most controversial sections (at least before the presidential election) Donald Trump comes in for his share of cultural critique. In the author’s view, his reality show The Apprentice opened the door to making icons out of mediocrity, both in its host and revolving cast. She finds a link between the Trump television brand and offensive white trash shows like Duck Dynasty, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, and Paris Hilton’s remake of Green Acres dubbed The Simple Life. The hypothesis needs testing, though. This reviewer admits ignorance of such crude populist fare, nor is she prepared to sample their contents.

An excellent choice for general readers, scholars, and Working-Class Studies courses, the volume also provides a bibliography as exhaustive as the discussion itself. Endnotes too are appropriately legion. One comes away from this reading experience with the view that the time is right for an expansion of whiteness studies to the subjects whose so-called white privilege barely existed.