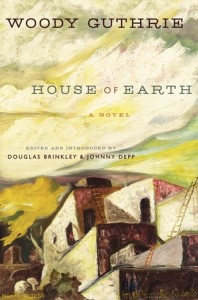

House of Earth

House of Earth

by Woody Guthrie (Harper Collins Publishers, 2013)

A gritty, poetic struggle to survive under capitalism

Book Review by Joshua Barnett, an architect at the NYC Housing Authority, union steward with DC 37, and member of the Executive Board of the NY Labor History Association.

One year. And what is a year? A year is something that can be added on, but can never be taken away. Yes, added on, earmarked and tagged, counted in signs of dollars and cents, written down the income column and across the page with names, and photos can be taken of faces and clipping on to the papers, and the prints of the new baby’s feet can be stamped on the papers of the birth and the print of the thumb going back to work can be stamped onto the papers that say it is a good place to work. And a year is work. A year is that nervous craving to do your good job and to draw down your good pay, and to join your good union….And a year of work is three hundred and sixty-four, or –five, or –six days of the run, the hurry, the walking, the bouncing, and the jumping up and down, the arguments, fights, the liquor brawls, hangovers, headaches, and all.

Such is the beautifully evocative, earthy prose from House of Earth, the only novel by radical organizer, poet, singer and songwriter Woody Guthrie, written in 1947 and just published posthumously in 2013. Guthrie writes of one young hardworking family during the Depression, Tike and Ella May Hamlin, their struggles to make a living off the land with the bank breathing down their neck every day, trying to keep body and soul together and have a child in a shack that can barely stand up to the beatings of the Texas Panhandle. He paints a sympathetic but clear-eyed and honest portrayal of working people, real people, not the noble but one-dimensional noble portrayals in the murals of the 1930s in the US and USSR, and certainly not the simplistic proles so condescended to in Orwell’s 1984.

The Hamlins rent a rickety house on decent farmland, but it’s an endless struggle to keep the crops coming up and food on the table, especially with their first child on the way. Tike’s dream is an adobe house—not a cheap wooden house built by the tight-fisted landowners that leaks and creaks and rattles in the wind, but a mud brick house literally made of earth that stands up to the climate and can’t be blown down, burned down, or repossessed by the bank. Tike sends away for a pamphlet from the government on how to build one, and keeps it in his pocket at all times.

It’s a book about struggle, but not a book about strikes and picket lines (with which Guthrie was intimately familiar). This is the day to day struggle to stay fed, clothed, housed and sane with the barest of tools. But then however heroic the efforts of the Communist Party and other organizers in fighting the ravages of the Depression in the 1930s as so openly depicted here, for most workers it was a constant struggle to hold on, even if that meant putting their faith in a dream like an adobe brick house. It’s hard to know if Guthrie really thought that was the solution, or was just using Tike’s dream of a solid roof to show how something so basic is so distant, since if it doesn’t generate profits it doesn’t get built. (Guthrie must have known something about building—adobe was, is, brilliant native design. Cesar Chavez spoke of living in an adobe house when he was young that was cool during the day and warm at night. Tike and Ella May would have been better off in a house of earth.)

What’s surprising for a book that’s gripping is that not a lot happens and there aren’t too many characters: Tike tries to get his house built, they work, and most importantly have a child. Aside from their conversations, sex, occasional interactions with the neighbors, a very faulty radio, there’s not a lot to distract from the constant work around the farm. But the lyrical descriptions of life on the farm, or life in general, the nuances of the characters and the tense, desperate scenes of childbirth on the open plains in the middle of a blizzard are so intense that myriad plot developments and a long cast of characters aren’t missed. For the most part Tike and Ella May don’t succumb to depression or defeatism, but that, too, is a constant struggle, with the bankers and threat of foreclosure that thousands of hard-working farmers faced during the Depression a constant black cloud over their lives, no matter how bright the real sky might be.

As the product of hardscrabble Oklahoma farmers, Guthrie clearly knew that being a worker isn’t a character trait. He’s not at all afraid to show both the strengths and flaws in his characters, from the diligent workers to their sometimes not-so-diligent neighbors, their tenderness and their less admirable traits, like Tike’s occasional sexism. And Guthrie being Guthrie he doesn’t shy away from straightforward dealings of sexual relations between a working class man and wife (if you’re from the city it’s a real education in the derivation of “roll in the hay”).

Such gritty portrayals of working class life are all too rare in American fiction, with exceptions like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Chester Himes’s If He Hollers Let Him Go, John Sayles’s Union Dues, Anzia Yezierska’s Bread Givers and Denise Gardenia’s Storming Heaven. But even they aren’t generally as frank as House of Earth in depicting the struggles, and illusions, of one working class couple trying to survive working land that isn’t even theirs.

It’s a rare book, all the more as the sole work of fiction from someone known as a songwriter, anything but didactic in its depictions of working class people and life, the choices workers make, their strengths and weaknesses, and the choices—however limited—people without money make under capitalism. As portrayed in House of Earth, the dream of something as basic as a house of earth will remain just that, a dream, as long as the bankers own the land, until we take it away and give it to the people who work it.