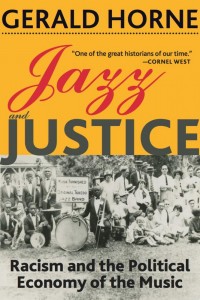

Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music

Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy of the Music by Gerald Horne

Review by Gregory N. Heires, senior assistant director of communications at AFSCME’s D.C. 37 in New York City and a Portside Labor moderator.

The literature on jazz generally focuses on individual artists, music analysis and the

music’s schools, such as bebop, post-bop and fusion. Historian Gerald Horne expands

the scope of the literature with his “Jazz and Justice: Racism and the Political Economy

of the Music”, by providing a deep look into the dark world of the jazz industry,

exploring the depth of racism and economic exploitation behind the music that has

brought joy to so many of us.

Horne charts the history of the music while explaining how it reflected the political developments and economic practices of our broader society.

He addresses the criminality of our economy, the Cold War, technological change and

civil rights. But a central theme runs throughout the book: With a predominately black

work force, the jazz industry has provided a ripe opportunity for music companies, club

owners, managers and the music mafia to exploit skilled workers in a unique sector of

our economy.

“As a professor, you want to break new ground,” Horne, who teaches African-American

history at the University of Houston and is the author of more than three dozen books,

said in an interview. “As a black person, you are trying to explain the difficulties we

have faced for centuries. That’s part of your obligation to humanity and the

community. This book is a large chapter about that reality.”

Relying extensively on oral histories, Horne recounts case after case of how jazz

musicians were stiffed out of their pay for club dates; were both locked out of and

received poor services from white-dominated unions; robbed of the copyrights of their

compositions; endured harsh working conditions; faced death threats and beatings;

put in long hours that led to physical ailments; needed to take on second jobs to

support themselves and their families, and suffered the indignities of racist practices of

hotels, restaurants and clubs.

Workplaces were often dangerous.

Lena Horne’s stepfather was beaten was beaten mercifully when he insisted mobsters

raise the singer’s pay. The violent setting of clubs led musicians to carry weapons to

protect themselves. For a while, Duke Ellington had a bodyguard.

“Everyone carried a gun, ”bandleader Count Basie said. He added, “patrons would

shoot each other, and if they didn’t like what you played, they shoot you.”

Crooked club owners and managers encouraged drug and alcohol abuse so they could

more easily rip off musicians. All this affected not merely the pocketbooks but also the mental and physical health of vulnerable musicians. Oscar Peterson suffered from

arthritis caused by his pounding of the keys of the piano.

Shocking instances of immoral treatment of jazz artists and personal tragedies and

indignities run throughout the 456-page book, including its 94 pages of footnotes

(which in themselves constitute a mini-book loaded with rich tales about the business

and musicians).

Saxophonist Charlie Parker died a pauper. Billie Holiday was told she was too light-

skinned to sing in the Count Basie orchestra. Pianist Bud Powell wound up in a

psychiatric ward after police savagely beat him on the head, creating permanent

mental health problems.

Gangsters pistoled whipped trombonist J.J. Johnson in a club after he came to the

defense of a women being insulted. David Baker was told that although he was the

best trombonist to have auditioned for the Indianapolis Symphony, he couldn't be

hired. Unable to support himself through his music, drummer Philly Joe Jones worked

as a trolley operator in Philadelphia during World War II.

Conductor Leopold Stokowski (widely known for the Disney film “Fantasia”) told a

young bassist Ron Carter that racist objections would prevent his hiring. Trumpeter

Charlie Shaver received $25 for his hit “Undecided.” As they toured the South in buses

during the 1950s, musicians like flutist Hubert Laws carried bottles to urinate into,

because they couldn’t use segregated facilities.

From the beginning, jazz has often been part of the dark side of capitalism. The new

music was born in the bordello culture in New Orleans. In the 1920s, many musicians

lacked control over their labor power as they were tied to bands and specific clubs.

Early in his career, Louis Armstrong gave up proceeds because of death threats, and he

was forced to pay fees for protection.

Mobsters controlled clubs. Crooked promoters illegally underpaid musicians.

Production costs were passed along to musicians. Hotel owners and rooming houses

overcharged blacks. “Jelly Roll” Morton frequently complained about being cheated by

the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Sadly, black musicians

were sometimes exploited by their fellow African-Americans, such as bandleaders like

Lionel Hampton.

To escape racism and economic exploitation, as early as the 1920s, black jazz artists

started to go into self-exile in Europe. Many remained for years in Europe, where they

escaped the indignities of racism and were able to earn decent wages. Soprano sax

player Sidney Bechet, pianist Fats Waller, alto saxophonist Benny Carter and tenor sax

players Coleman Hawkins and Dexter Gordon were among the most well-known of the

exiles who spent years living in Europe.

Technological change opened up additional ways to cheat musicians. The music mob

controlled the jukebox business. Radio stations gave little airtime to black artists.

The powerful music industry’s tight control of the distribution of music placed barriers

in the way of musicians who sought to protect their ownership and sales of their

products. Civil rights advocates fought discriminatory hiring practices of the music

industry.

Early on, Jim Crow practices made it impossible for black musicians to enter the

nightclubs business. Saxophonist, flutist and clarinetist Gigi Gryce abandoned his

effort establish a publishing company and record label as he faced harassment,

intimidation and threats from powerful interests with possible underworld

connections.

The U.S. government used black musicians as propaganda tools in the Cold War.

During the Cold War, the government sponsored tours in part to brunt criticism from

the Soviet bloc about the sorry state of civil rights in the United States. Musicians who

participated in the tours could, however, count on relatively decent pay.

Unions were a mixed bag for black musicians. Unions were segregated. Those open to

blacks often denied them full membership, which resulted in their pay inequity with

white musicians. When black unions merged with white unions, they lost control of

their treasuries and their leaders saw their power diminished.

While Horne generally paints a very bleak picture of the history of the political economy

of jazz, the history of the music includes many heroes, black and white, who viewed the

fight against racism as a personal crusade.

In 1957, for instance, white pianist Dave Brubeck canceled a concert in Dallas because

of segregated seating. Producer Norman Granz was widely admired for providing just

compensation to musicians. Cuban composer Mario Bauza promoted greater diversity

in orchestras and improved union representation. Singer Paul Robeson came under

attack for his defense of musicians. Drummer Max Roach and his wife Abbey Lincoln

were deeply involved in the civil rights movement.

Cuban percussionist Machito’s decision to call his band the “Machito & His Afro-Cuban Orchestra” was in itself a bold political statement. Producer. John Hammond

denounced the “shocking exploitation of recording artists.” Harry Bridges of the anti-

racist International Longshore and Warehousemen’s Union called James Petrillo, head

of the musicians’ union, and threatened to form a competitor union if speedy reforms

didn’t happen.

During the civil rights era and the political upheaval of the 1960s, progressive jazz

musicians also faced a backlash for their outspokenness, perceived radical recordings

and activism. They used their compositions as expressions of protest. Rollins released “Freedom Suite” in 1958. Two years later, “We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Suite” came

out. Yusef Lateef composed “African American Epic Suite” about slavery and the Middle

Passage. Prominent artists were involved in the anti-imperialist and black nationalist

movements.

Today, the pernicious Jim Crow practices are gone. Our colleges and universities are

helping preserve jazz. Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City has helped the music

achieve greater respect.

But, sadly, economic challenges remain.

Like the film industry, the jazz world is deeply polarized with an elite of successful

musicians and a much larger number of artists who cannot support themselves. Jazz

players must teach and take on jobs outside their profession to survive economically.

Advances in technologically—the spread of streaming music with scant remuneration

for the artists—is robbing jazz and other musicians of the full value of their work. Jazz

orchestra leader Maria Schneider, a leading advocate for musicians and their

copyrights, is a beacon of hope. But fans need to become better advocates for jazz

artists in their struggle to gain greater control over the production, distribution and

sale of their music.