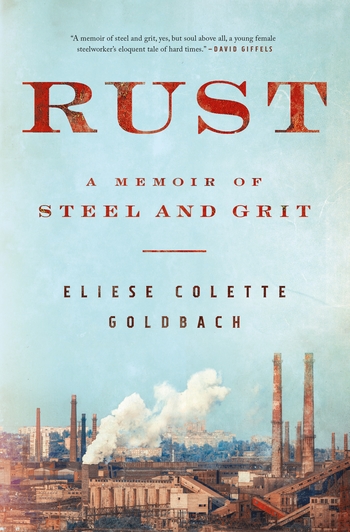

Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit

Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit by Eliese Colette Goldbach (New York: Flatiron Books, 2020)

I relocated from Cleveland to New York many decades ago. Not long afterward, a friend playfully interrupted me while I was telling a story: “Susan, when you say “gal,” everyone will know you’re not a native New Yorker. No one uses that word here.” My defense then, as now: I stand accused. As a former Clevelander, raised in the industrial environment that is now known regionally as the “Rust Belt” of America, and having a brother who worked in a steel mill there, I could relate easily to the world of “rust” where this memoir takes place.

Rust: A Memoir of Steel and Grit is a narrative of the author’s circuitous and bumpy journey to adulthood and securing a productive place in society. Born and raised in a working-class family near the old, dilapidated steel mills of Cleveland, Eliese Colette Goldbach received a traditional and insular Catholic education, subsequently enrolling in a small Franciscan university in Ohio. Her difficult educational and career choices were further complicated because she suffered bi-polar disorder. Though doing a fair share of whining about herself and others, nevertheless Goldbach’s inborn spunk and grit gradually led her to find a path to a more fulfilling life.

Goldbach describes her family as well as her religious, educational, personal, and work experiences. She explains her ghastly rape while attending the Franciscan university, as well as her need to survive after withdrawing from college, living in unlivable housing and struggling with low-paying jobs. Being academically gifted yet not finding work that suited her, she did what she and many others in such circumstances do to survive: she worked as a house painter and, eventually, to earn even higher wages, as a union steelworker (#6691: Utility Worker) at ArcelorMittal Cleveland, known to all older Clevelanders as the site of J&L (Jones and Laughlin) Steel.

Goldbach clearly finds her voice in telling of her new-found fortitude and footing while working as a steelworker. She describes her jobs in various departments – all of them incredibly miserable, difficult, and dangerous. She consistently speaks well of her union and her union brothers and sisters. I was pleasantly surprised not to read about any troubles of sexual harassment or discrimination in the mill while enjoying her depictions of solidarity that she experienced with her co-workers.

She also describes her political views, which differed greatly from those of her parents, causing much difficulty. The backdrop for this part of the book is the Republican Convention of 2016 (no comment from this reviewer), which took place in Cleveland. But most important to her story, Goldbach explains her episodes with bi-polar disorder and the need to obtain medical help while trying to hold onto her full-time, 12-hour-shift job. As if being a member of the working class and surviving financially isn’t challenging enough, this book illuminates how much more difficult life is while coping with such an illness.

Most of the narrative is devoted to her work in the steel mills and seeing the factory through her eyes: not just the frightful flames billowing from its decrepit smoke stacks, but its beauty, too, in helping to mold her, like the shining rolled steel leaving the mills, into a better life. She returns to college, completes her degrees, and eventually joins the faculty of a local Catholic university.

I enjoyed reading this “steel and grit” memoir. Goldbach strived for success and security and did in fact find her true career, as well as establish comfortable relations with her family and her boyfriend while managing her medical needs. I would have liked seeing images of the factory worksites, which were sometimes difficult to visualize, as well as photos of her, her family, and friends. Perhaps if a new edition is published, these things will be included. In the meantime, enjoy this first-edition memoir of a successful, working-class gal.

Reviewed by Susan E. Wilson, a retired education director of AFSCME Council 37/1707 who previously worked in the fields of work force development, higher education and government affairs. She serves on the Board of the NY Labor History Association.