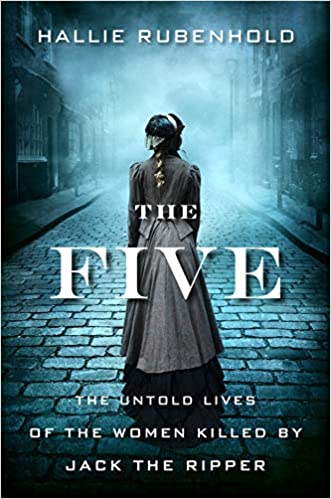

The Five: The Untold Story of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper

The Five: The Untold Story of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper, by Hallie Rubenhold (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020)

Polly Nichols. Annie Chapman. Elisabeth Stride. Kate Eddows. Mary Jane Kelly. Not famous names. But real people, known only for their deaths because their lives were eclipsed by their far more famous murderer. Histories of Victorian England typically focus on the famous, the infamous, the male, the rich, the factories, the empire; not the women, the people, who are usually only portrayed as the backdrop. “He murdered prostitutes.” So read the narratives and endless stream of mystery and horror films about Jack the Ripper. But what does that actually mean? And how do we get past the implicit misogyny and preconceptions about life in capitalism’s lower depths contained in that assumption to see the real people involved?

Polly Nichols. Annie Chapman. Elisabeth Stride. Kate Eddows. Mary Jane Kelly. Not famous names. But real people, known only for their deaths because their lives were eclipsed by their far more famous murderer. Histories of Victorian England typically focus on the famous, the infamous, the male, the rich, the factories, the empire; not the women, the people, who are usually only portrayed as the backdrop. “He murdered prostitutes.” So read the narratives and endless stream of mystery and horror films about Jack the Ripper. But what does that actually mean? And how do we get past the implicit misogyny and preconceptions about life in capitalism’s lower depths contained in that assumption to see the real people involved?

Hallie Rubenhold shows us how in her major breakthrough work, The Five, The Untold Story of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper. It doesn’t focus on Jack the Ripper, but on the victims, their circumstances, what drove them into destitute situations where they could easily fall prey to violence. By putting faces on the faceless she not only gives a vivid reality to the lives of working people, but also tears down assumptions about them.

These were women, typical of millions of people in late 19th Century England, on a downturn into poverty and homelessness. As Rubenhold graphically illustrates in the five narratives, the safety net for impoverished workers, especially women, in Victorian London was threadbare to the point of transparency. There were shelters, of a sort, but people had to surrender themselves to the workhouses or almshouses, were given meager rations, forced to work long hours at little or no pay, and separated from their partners, children, or both.

Interestingly, the women murdered by Jack the Ripper weren’t young women lost in a giant urban setting. Polly Nichols was 43, Annie Chapman 47, Elisabeth Stride 45, Catherine Eddows 46; only Mary Jane Kelly (and the only one who might have spent time as a full-time sex worker), was young at 25. They had all left or lost their marriages, and that too was often a matter of survival. Work options for women in late 1800’s England as described in The Five were slim—seasonal farm work, domestic help, factory work, possibly teaching if educated. The material incentives to stay with a man were strong, as was the social pressure. Divorce was frowned upon and difficult to obtain. Alimony and child support were rare, and rarely enforced.

But still, women would leave or be forced out of marriage, especially in a dull, stifling, or abusive situation, hoping for help from relatives or the few economic options available. Or men left women, in which case the wife might have some recourse to the courts, but could still expect a difficult time, especially if children were involved. These women lost their married lives, and the descent into a precarious homelessness was more or less inevitable, given the living conditions of industrial revolution capitalism. Dickens wasn’t exaggerating.

The sexism of the past historiography of the murdered women is a key factor that Rubenhold addresses explicitly. The murder of “prostitutes”, as described in narratives of the murders from the tabloids of the 1880s to now, carries an implicit, sometimes explicit, stigma of someone somehow morally lacking; in dire circumstances supposedly to a degree of their own making. Sex work and sex workers are still often the subject of latter-day Victorian judgment (including sometimes labor circles and the left). In reality the victims’ post-marriage relationships were for the most part means of support and survival.

Usually any narrative on Jack the Ripper is spent speculating who he was. The author doesn’t spend time on that. She doesn’t even spend time on the actual murders. She spends her time on the women. Her research is vivid in detail and the writing fluid so at the end of each chapter there’s a sense of loss, sadness, and anger as if reading a headline today. Through each one the book portrays the struggles of millions of working-class women, and men, in a way that adds a human and humane aspect to still-vital broader histories such as Frederick Engels’ The Condition of the Working Class in England (1844).

Her book resonates today in the international horror of sex trafficking. Left to itself post-industrial capitalism doesn’t offer poor women much better choices than industrial capitalism did. Excellent working-class histories, on old and new subjects, come out all the time. But it’s rare that a book comes along and you say where the hell has this been? The endless parlor game of who actually was Jack the Ripper seems even more pointless after reading The Five. Interest turns from who the murder was to who his victims were, and that’s the success of Rubenhold’s history. The book is dedicated to them, and more than lives up to the dedication.

Reviewed by Joshua Barnett, an affordable housing activist, architect at the New York City Housing Authority since 1999, union rep in Local 375, DC 37, AFSCME, third-generation unionist and Brooklynite.