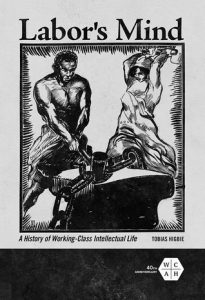

Labor’s Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life

Labor’s Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life, by Tobias Higbie (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2019)

Labor’s Mind: A History of Working-Class Intellectual Life, by Tobias Higbie (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2019)

The question of how working-class activists became militants, leaders and organizers is one we may have wondered about: in our own lives and in the lives of people who join the movement, and we hope will become life-long activists. There are many ways to narrate of this process. For some it has been the experience of exploitation that leads them to ask why they live without, in a society of plenty; for others they have been prepared for a life of activism by their parents; and still others may describe an “Amazing Grace” experience – a transformation that is like being hit by lightning and being transformed by it. Historians and especially historians of the labor movement have not given this issue the attention it deserves.

Historian Tobias Higbie has addressed one aspect of these stories by examining the role of reading, and the ways that workers entered into the world of analysis, perspective, and ideology. In the formation of both US labor activism and US radicalism, this process was critical. It is a book that was calling out to be written, and Higbie has answered this call admirably. The book is a series of connected essays about different expressions of working-class intellectuality. At the same time, he maintains a critical eye, as he explores not only the “what” of working-class learning, but the different forms in which working-class knowledge was expressed.

In each chapter, he looks at different aspects of working-class literate culture. He writes in Part 1-“Reading the Marks of Capital” chapter focuses on different sites where working-class intellectuality emerged: individual reading; public open forums and lectures, workers’ schools and colleges. In Part 2 -“Imagining Critical Consciousness” his chapters are “Brain Workers in the House of Labor” and “Icons of Ignorance and Enlightenment: The Visual Culture of Critical Consciousness.”

There are two thematic questions that form the background of each of these explorations. The first is the way working-class leaders narrated their own lives. He found there were often competing tropes in individual stories. On the one hand, there is an anti-intellectual framework in which learning in the “school of hard knocks” was more important than formal education. On the other there are the often very specific stories of how reading helped them to understand not only the nature of exploitation and oppression (one could learn this on the job), but how to understand the system as a system, and the ways to change it. My favorite is from James Maurer, Pennsylvania Socialist and Labor leader, and Debs running mate for Vice-President. In his autobiography, It Can Be Done (1938), Maurer describes how, as an illiterate young worker, he was taught to read by an old Knights of Labor activist who gave him labor newspapers and pamphlets.

A second issue that threads through these essays is the relationship between the established universities and the efforts of workers’ self-education. Radical critics of university life since the 1960s have pointed out the class bias (along with race and gender bias) inherent in both the structure of institutions of higher education, and in the content of the classes and research. However shocking this might have been after the post-WWII “democratization” of the university, it is important to remember that these institutions began as projects of elite class-consciousness. Because of this, many workers and their leaders did not believe that universities had any role to play in improving their lives. As institutions like the Wisconsin School for Workers became incorporated in the University, and as other institutions began adding labor as a subject for study, they became institutional sites for labor education. The temptation of a connection to the universities, for the labor movement, was both the aura of respectability that was a prime characteristic of higher education, and the newly conceptualized belief in education as a means of upward mobility. Higbie seems skeptical of this process and shows how education for “class struggle” came, in the universities, to be education for “class peace”.

Higbie mines wonderful sources including the autobiographies of radical leaders such as James Maurer, William Z. Foster, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. He also examined the essays that workers wrote as part of their application to workers’ education programs such as Brookwood Labor College, the Bryn Mawr School for Women Workers, and the Wisconsin School for Workers. In these essays, workers described the process whereby they became interested in furthering their education. In other sections he looks at how class-consciousness was presented in the cartoons in the labor and radical press. A section that was especially fascinating to me, Higbie discusses a production of Karel Capek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots) at Brookwood Labor College, and the complicated ways that labor activists saw technological change.

This is a book for current labor activists, union members, and radicals. It asks the important question of how do we all change and learn in ways that can advance the project of working- class emancipation. Today education for working class people, including higher education, is presented as job training and an avenue for upward mobility. We all, workers or intellectuals, or both, need to remember that our labor forebears imagined education as liberating. It still is a good idea.

Reviewed by Paul C. Mishler, Associate Professor of Labor Studies, Indiana University