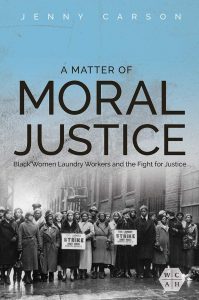

A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice

A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice, by Jenny Carson (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2021)

A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice, by Jenny Carson (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 2021)

Black Women Activists in the Pursuit of a Democratic Union

There is no question that Black women workers in this country have experienced and continue to experience discrimination in the workplace. Focusing on Black women laundry workers in New York City, Jenny Carson convincingly argues that these women workers did not necessarily succumb to racism and sexism by their employers or even by white male union leaders. Instead, they resisted discriminatory treatment at work and in their communities. A Matter of Moral Justice: Black Women Laundry Workers and the Fight for Justice documents Black women labor activists’ multiple attempts to organize laundry workers that began in the early twentieth century.

Carson’s ability to synopsize the industry’s complex history is especially impressive. She traces the evolution of the industry from its origins with the Troy collar workers in the 1850s to the peak years of the 1930s when New York City’s power laundries employed more Black women than any other industry in the United States. Aptly situated in the historical context, Carson explains how laundry workers, many of whom had migrated to the northeast during the Great Migration, benefitted from the prolabor legislation in the Second New Deal. They enjoyed a heyday when they received support from the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and, by extension, from the Congress of Industrial Organizations. As for virtually all American workers, the war years came with opportunities for advancement but in the postwar years most of these hard-won gains were negated. The acquisition of electric washing machines by housewives and coin-operated machines installed in urban apartment houses during the 1950s cut into industry profits and further disintegrated the workers’ bargaining power. Nor does the story of unionization end happily. By the 1970s the Laundry Workers Joint Board is all but “a shell of its former self.” There are however valuable insights pertaining to labor organizing that reveal themselves throughout Carson’s detailed account.

Organization of the carefully constructed chapters, each with its own brief introduction and conclusion, helps the more general readers navigate complicated events involving multiple historical actors. Chapters are arranged chronologically, almost all with a helpful subtitle. “A Miniature Hell: Working in a Power Laundry” (Chapter 2) is a particularly informative chapter. It does what its title suggests—exposes the horrendous conditions in the laundries but it does so by explaining what each job entails. In this way, the reader comes to understand the industry’s occupational hierarchy where Black women are crowded into the lowest-skilled and lowest-paying jobs including ironing, shaking, sorting, handwashing, marking and folding. Black women most often worked as flat ironers or “mangle girls,” feeding linens and clothing items into hot noisy machines. Men on the other hand, made more money and tended to be drivers (almost always white men) and head washers with little concern for the women’s circumstances. In addition to low wages and industrial accidents—fingers lost to machinery or broken limbs from slipping on damp floors—employers preyed on Black women workers. By the end of Chapter 2, readers not only learn about the laundry industry’s technical processes, but they fully comprehend what it means to be a laundry worker in New York City.

Carson speculates that the early twentieth-century garment workers’ uprisings may have inspired the laundry workers’ attempts to form their own unions. Despite the support that women such as Rose Schneiderman of the Women’s Trade Union League provided, the laundry workers’ racially and ethnically diverse workforce made for a perplexing search for worker solidarity. Financial concerns also hampered efforts to unionize. There was the question of how workers would survive from day to day during strikes. Moreover, the married women and older women who comprised a significant sector of the workforce in the laundries feared losing their jobs because the industry was one of the few that would hire them. It comes as no surprise then that the workers’ early union drives met with limited success. Employers on the other hand used strikes as an excuse for opportunistic mergers so that so they could fortify their companies in preparation for future union drives.

Affiliation with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America proved in the long run that although most union leaders may have been less racist, it did not mean they were less sexist. One only has to peruse the rosters of the union’s executive board for evidence. A few exceptional white women organizers in the Amalgamated such as Bessie Hillman and Gladys Dickason did reach out to Black women activists; however, racial and gender divisions persisted. But by the late 1930s after securing adequate financial resources from the union and having built solidarity in the workplace, Black women laundry workers helped to organize approximately 30,000 laundry workers.

It is in telling the individual activist workers’ stories where Carson shines. By the time the Laundry Workers’ Joint Board was established in 1937, Trinidadian-born Charlotte Adelmond had been organizing laundry workers for years. Known for her unconventional attire and organizing tactics, the least of which involved headbutting obstinate bosses, Adelmond amassed a popular following that resulted in an expanded union membership. As the business agent for Brownsville’s Local 327 she was the only woman in the laundry workers’ union to hold a leadership position. Whereas some considered Adelmond’s organizing approach radical, her younger colleague and fellow unionist, Dollie Lowther Robinson used more traditional strategies when interacting with union leaders or rank and file workers. Robinson, an activist from her teen years forward, received a law degree from New York University. She accepted personal and professional help from the Women’s Trade Union League and from Bessie Hillman. Robinson became the ACWA’s Education Director and was eventually employed by the Women’s Bureau during the Kennedy administration.

Like Adelmond, Robinson also endured discrimination as she ascended through union ranks. Ultimately however Adelmond’s path spiraled downward when union leaders sought revenge after she publicly confronted a racist union official. Her willingness to speak out coupled with the perceived threat she posed to male leaders ended in Adelmond’s suspension, demotion, and finally in her resignation from the organization. Neither woman fought solely for working-class women’s rights. They both entered the larger arena of civil rights while their continued efforts to infuse the rights of women and people of color into the union met with opposition from all but a few of the male union leaders.

Although Adelmond and Robinson fell short of challenging the exclusionary practices that relegated driving and head machine washing positions to men, they are representative of the numerous women who fought and still fight every day for better workplace conditions. Even in the twenty-first century, laundries now often connected to linen supply companies that service hotels and hospitals are still dangerous places to work. Management promotes a racist and sexist work culture that exploits immigrant, Black, and women workers. Laundry company owners use retaliatory tactics to prevent unionization. Despite these persistent issues, Carson contends that there are lessons to be learned from the laundry workers’ story. Union organizers need to take these lessons into consideration as they move forward. It takes more than financial support and a sense of solidarity to organize twenty-first century rank and file workers. Activists need to act aggressively when they reach out to workers, particularly to people of color in their local communities. More specifically they need to go into the churches and participate in the political sphere in ways that benefit workers. Today more than ever workers need to remain optimistic as they persist in working toward a democratic and morally-just union for all.

Reviewed by Karen Pastorello, who recently retired as the Chair of the Women and Gender Studies Program and Professor of History at Tompkins Cortland Community College (State University of New York). Her books include: A Power Among Them: Bessie Abramowitz Hillman and the Making of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (University of Illinois Press, 2008), The Progressives: Activism and Reform in American Society, 1893-1917 (John Wiley and Sons, 2014), and Women Will Vote: Winning Suffrage in New York State co-authored with Susan Goodier (Cornell University Press, 2017). Her current project explores the life of Mary Elizabeth Pidgeon, Director of the Research Division, Women’s Bureau, United States Department of Labor (1926-1956). Karen can be reached at pastork@tc3.edu.