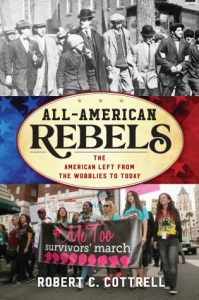

All-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today

A ll-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today

ll-American Rebels: The American Left from the Wobblies to Today

by Robert C. Cottrell (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020)

Robert C. Cottrell is not the first historian to survey left-wing American activists in recent decades, but he is perhaps the most ambitious and up to date. In crisp, concise prose he discusses them, and notes that they include a “wide array of movements,” relating to issues concerning “the rights of women, gays, and others in the 1970s and 1980s.” Reflecting an amazing talent for synthesis, Cottrell, the author of more than twenty books, reminds the reader of dissent’s place in American history, and provides a wonderful, informative bibliography, but no source citations or illustrations.

His book opens with a discussion of the socialist visionaries, labor organizers, and industrial violence during the late nineteenth century from the post-Civil War era to the First World War. It was a time when Edward Bellamy, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and numerous other writers exposed social and economic conditions that prompted action that ushered in the Progressive Era. Among these critics were the visionaries who comprised Greenwich Village’s “Lyrical Left” and the dissenters who opposed the entry of the United States in the European War and then endorsed the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. “Repression, sectarianism, and mortality tore apart the early American left of the twentieth century,” is how Cottrell summarizes government and society’s reaction to them. On the other hand, they did receive support from a new American Fund for Public Service (or Garland Fund) and American Civil Liberties Union.

Cottrell’s emphasis on the American left is significant in good part because it counters the belief commonly held by many Americans in the early twentieth century and even today that the ranks of radicals were dominated by foreigners. Such thinking has contributed to nativist legislation and two Red Scares. In truth most immigrants tend to be conservative. As Cottrell makes evident, dissent is often home-grown.

Associated with violence especially since Chicago’s Haymarket Affair of 1886, the years that included the Depression and the Second World War vexed and split the left. Divided between Stalinists and Trotskyists, and competing for attention with Socialists, Communists strove to exploit the travails of American capitalism and surmount the enormous popularity of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. In addition, some served the interests of the Soviet Union, via espionage as well as ideological obedience, and agonized when confronted with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939. Cottrell is no apologist for them, brilliantly describing their travails as well as those of the artists, writers, pacifists, interventionists, and others first dealing with economic calamity and then world conflict. He describes these years of the “Old Left” and “Popular Front” in one chapter before addressing the Cold War and his primary concern, the 1960s and beyond, the subject of the next six sections.

With a sharp eye for detail and recognition of countless individuals and organizations Cottrell takes his account to 2019. Five years later it is tempting to lament the omission of incredible events that have occurred since then. Yet it is fascinating to note a sense of continuity. A close reading reveals that the “Me Too” movement, calling attention to sexual abuse, dates from 2017, and the anti-Zionist cry, “From the river to the sea/Palestine will be free,” was shouted the next year, six years before the massacre of October, 2023 and Israel-Hamas War. As traumatic as the 1960s were, they are brilliantly described in their fury, and it is instructive today to be reminded of their turbulence.

Reviewed by Professor Robert D. Parmet, York College of the City University of New York