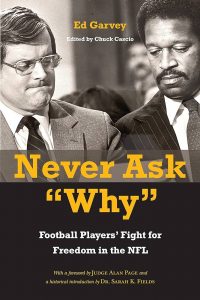

Never Ask ‘Why’: Football Players’ Fight for Freedom in the NFL

Never Ask ‘Why’: Football Players’ Fight for Freedom in the NFL, by Ed Garvey, edited by Chuck Cascio. Temple University Press. 2023

Never Ask ‘Why’: Football Players’ Fight for Freedom in the NFL, by Ed Garvey, edited by Chuck Cascio. Temple University Press. 2023

Although the key actors in this book are famous NFL players, it is definitely not a sports book; it’s a labor history book about the difficulties of organizing a union. The workers in this case are marvelously athletic human specimens who once a week expose their bodies to risk, all for the glory of the game and wages they might earn. These workers are different in one way from factory workers, laborers or medical staff; their bodies are owned lock, stock and barrel by one gigantic, wealthy monopoly that has enslaved and exploited them.

And, as this book shows, these players (great and not-so-great alike) face punishment if they dare to wonder why their bodies are owned by someone else. Once claimed by an NFL club, the player has little choice but to play for that club and that club alone, unless the ownership wills it, most often through a trade.

The monopoly, of course, are the 32 owners and managements of the football teams that make up the National Football League, all of whom watch from the warm suites high above the playing field, echoing the roles of emperors of the Roman Empire, ready to show “thumbs down” to any player who would start talking union or begin to ask tough questions.

The author, Ed Garvey (1940-2017), was the first executive director of the National Football Players Association and in his 12 years (1971-1983) built a strong union that won collective bargaining agreements to weaken the hold that the owners of the teams had on the players’ lives and playing fortunes. As an autobiography, it is a book that deals only with the events of Garvey’s years as executive director. It is told from Garvey’s point of view, complete with his views of heroic players whose union activities cost them their playing careers as well as those players who were less courageous. Garvey minces no words as he spells out the cowardice of the players who would break solidarity or the duplicity of the owners who time and again broke their word or outright lied.

Anyone who has participated in a union organizing drive will see the tactics employed by the NFL owners are largely identical to the tactics used by any manufacturer, hospital or Starbucks in opposing unionization. As in most organizing campaigns, the NFL owners would plea to the players that they are a “family” headed by a benevolent father and that the union organizer is an “outsider.”

Then there’s the ultimate tool used to bust up an organizing drive or to doom it to failure: the discipling or firing of the union sympathizer. The NFL did this repeatedly, and since the owners basically had the power to decide whether a player makes the roster, they could do this easily. It often didn’t matter if the player was key to the team; if he was talking union he was gone.

Quarterback Joe Kapp, who in 1969 had led the Minnesota Vikings to its first Super Bowl, was a particular hero of the story. He refused to sign a standard players agreement after being traded to the New England Patriots, and as a result was banned from the league and ended up playing in Canada. His case was decided by Pete Rozelle, then commissioner of the NFL, who acted as “arbitrator” in all cases involving players. Garvey found this practice of the chief NFL executive acting as “arbitrator” to be grossly unfair and spurred Garvey to focus on ending the “Rozelle rule.” The story of how Garvey helped to weaken the Rozelle Rule is told in detail, almost like a war story.

Garvey all but lionized John Mackey, once called the game’s greatest tight end, who was waived by the Baltimore Colts for a dispute he had with the team ownership. He also was president of the NFLPA. When none of the other teams would pay the $100 needed to pick up Mackey’s contract, his career ended – an obvious clue to the conniving, monopolistic nature of the league’s ownership to blacklist the star.

Onetime Green Bay Packer Center Ken Bowman (a University of Wisconsin graduate) was also a victim as his union activities caused him to be booted from the league.

Garvey, a native of Burlington, Wisconsin, graduated from UW Law School, and was working for a Minneapolis law firm when the fledgling NFLPA leadership called seeking legal help. Their call had another Wisconsin link; Garvey was recommended by Nathan P. Feinsinger, the late UW law professor, who had won renown as a labor mediator.

Garvey left the NFLPA in 1983, returning to Wisconsin, where he ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for U.S. Senator in 1986 and for governor in 1998. He died after a long struggle with Parkinson’s disease. The book was edited by Chuck Cascio and published posthumously.